Australia's Folk-Songs by Percy Jones

THESE last few years have witnessed a welcome and long overdue interest in Australian historical research. For far too long, this aspect of Australiana remained the Cinderella of Australian publications. It is therefore not very surprising to find even knowledgable people taking for granted the statement that "Australia possesses only one folk-song, 'Waltzing Matilda.''' There has been a great deal of printers' ink spilt over the authorship of this popular song, but to my mind, this energy could have well been diverted into a much more important channel of research – namely, the rescuing from oblivion of the large number of other folk-songs which were characteristic of the pioneering days of this country.

THESE last few years have witnessed a welcome and long overdue interest in Australian historical research. For far too long, this aspect of Australiana remained the Cinderella of Australian publications. It is therefore not very surprising to find even knowledgable people taking for granted the statement that "Australia possesses only one folk-song, 'Waltzing Matilda.''' There has been a great deal of printers' ink spilt over the authorship of this popular song, but to my mind, this energy could have well been diverted into a much more important channel of research – namely, the rescuing from oblivion of the large number of other folk-songs which were characteristic of the pioneering days of this country.

There will be many, of course, who will question the importance of such research. It will be regarded by musical and poetical highbrows as beneath their attention and by historical scholars, enveloped in their fetish for superficial practicalities as of little, if any, importance in Australian history. For many years, I have tried to impress upon teachers the necessity of co-relating the school-music periods with those of history, literature and geography. "Give me the privilege of writing a nation's songs, I care not who makes her laws," has an application other than the obvious. Not only can the songs of a nation stir its people to the nation's ideals, but they enable other nations to learn and appreciate the spirit of a country far more vividly than the mere study of historical dates and events.

The real national songs of the different peoples who inhabit the British Isles make the struggles of those peoples more intelligible and abiding than a chronicle of wars, while the "aisling" songs of Eire and Scotland tell us more of what the Stuarts meant to the people than any dry text-book. Were there more general love and appreciation of the art of foreign countries there would be far less international hatred, because it is extremely difficult, if not impossible, to have a lasting enmity towards a people whose art one admired and loved. Hence, it is important that in the school-music periods songs be chosen which will fill out and intensify the knowledge of countries which are studied by the children in their other school periods. And so it is with Australia. It is true that we are a very young country; that what traditions we have are not very old, but precisely for this reason should we treasure and preserve what little we have. Growth is gradual in every sphere of life, and in no other sphere is this more true than in the growth of a nation. Everything that contributed to the life of Australia in its early history is important, and it is for us to preserve all we can of early Australia before it is too late.

As far as the words of our early songs are concerned, "Banjo" Paterson's "Old, Bush Songs," published by Angus and Robertson, is the most important collection we have. The eighth edition of this work was published in 1932, but has been unobtainable for years. Recently, "Australian Bush Songs and Ballads," edited by Will Lawson, was published by Frank Johnson, but for the most part this is a collection of ballads by later authors, many of whom are still living. Of the eleven earlier songs whose authors are unknown, more than half had already been published in the Paterson collection. Other than a few scattered references in newspapers of one form or another, the only other collection with which I am familiar is a very good series of "Australian Bush Recitations" by Frank Reed ("Bill Bowyang") of the "North Queensland Register." Some of these recitations were originally songs, but many of these, too, are to be found in the Paterson work. It must be obvious, then, for at least three reasons, that there is still much work to be done in saving these songs. First of all, Paterson did not exhaust all the shearing of bush songs, even of New South Wales. This was no fault of Paterson's. As these songs were passed from one to another by word of mouth, there was no other method of collecting them than to go around the various sheds and towns and copy them down from the singers. It is not to be wondered at that many have never yet been printed. Secondly, in his collection, there is but one song of the "diggings." Although the atmosphere of the various "rushes" did not provide the peace and tranquillity of the camp-fire or the farm-house verandah, which would be more congenial to song, man's innate desire to record happenings in ballad form would hardly have gone unrealised when there was so much of interest to record on the "diggings." Here, then, is another group of songs as yet unexplored.

But more important again is the fact that the tunes of many of these songs are being forgotten. Paterson generally recorded the name of the tune in his collection if it were a parody on a well-known tune, whether English, Irish or Scottish, but where the tune was original or unknown. he was at the same disadvantage as many others. It is simple enough to write down the words of a song, but it is another matter to write down the music. Almost without exception, the shearers and others who sang these songs could not write a note of music. The tunes were learnt by heart and handed down, but no attempt was made to put them on paper. In collecting these bush songs from various correspondents, the same phrase occurs time and time again in their letters: "I know the tune but I can't write music." There is only one way to gather these tunes, and that is to have them sung and taken down by someone who knows music. Unless this is done before the generation which remembers them dies out, they will be lost for all time. There are difficulties, of course, with such dictation. There will be variants of the same tune just as there are variants of the words. Paterson himself was faced, with this difficulty and he followed the rule of choosing the variants which best fitted the metre of the particular verse. As a rule, this was sound enough, but in quite a number of instances I have found that when the words were sung, variants which he rejected were better suited to the song than those he chose. Although in the end, such variants are of minor importance, nevertheless, they are a constant worry to an editor. With the dictation of the tune a further difficulty is encountered-namely, that the people who remember the tune are now fairly advanced in years and variants creep in with the lapse of time. Moreover, with older people, intonation is not always accurate and time-values are often difficult to determine. Lastly, every collector of folk-lore is faced with the travel problem. In a continent the size of Australia, it would be a full-time undertaking for several years to comb the six States thoroughly for old tunes. The only completely satisfactory solution would be for the Commonwealth Literary Fund to make a grant to some person technically equipped for three years, or longer if necessary, so that this aspect of early Australian life is preserved to posterity. In the meantime, any of us who have the opportunity to gather any of these songs at all would be doing a national service to retrieve some of them before it is too late. Although I have not had the time at my disposal to gather as much of the material as I would like, I have collected sufficient to form certain impressions which may prove of interest.

THE MUSIC

The tunes to which these early songs of Australia were sung fall into two main categories. Many of them were simply sung to tunes which were not original, but were in vogue in parts of the British Isles as well as here; others were original melodies composed specifically for the new songs. These latter are, of course, of much more interest than the others as reflecting the life of the pioneers. But let us take the parodied melodies first. These are important, for they indicate to some extent the proportionate extent of the various racial influences among the balladists and their friends. The honours seem to be fairly evenly divided between England and Ireland. Numerically, there is a slight preponderance of English tunes, but quite a few of these were, so to speak. common property, so that an accurate estimate is very difficult. There are typical English tunes such as "So Early in the Morning," "Little Sally Waters," "It's a Fine Hunting Day," side by side with drawing-room songs of the period like "She Wore a Wreath of Roses." Among the numerous Irish songs there are, for example, "O'Donnell Abu," "Irish Molly O," "Rory O'More," and "Barney O'Keefe," while there is no knowing how many songs were sung to the tune of "The Wearing of the Green." Nothing pretentious, to be sure, but they served the purpose. All the balladist wanted was a tune that was easy to sing while he told his story. One rather interesting fact is the almost complete absence of any Scottish songs. There may be some which have not come my way, but the only one so far encountered is a rather clever and delightful parody on "John Peel" about the Kookaburra. It begins:

D'ye ken our Jack with his note so gay,

D'ye ken our Jack at the break of day,

D'ye ken our Jack though he's far, far away,

On a ring-barked tree bough in the morning?

Most of the tunes selected by the balladists were of the lilting type, easy to sing away as the singer worked or sat on his dray or squatted for the night with a camp-fire nearby to keep mosquitoes away. There are a few of the sentimental type of the period, lyrics set to such tunes as "Ben Bolt," but these form a small minority.

Coming to the tunes that are original, we have a much truer reflexion of the character of these songs. Some of them are, naturally enough, reminiscent in parts of some of the simpler "Come all ye" type of song popular in Ireland. In fact, a study of a number of the tunes written specifically for our early bush-songs leads to the inevitable conclusion that our early melodies grew out of the Irish "Come all ye." It was a development or an adaptation of this easy form of balladry to new conditions of life. Melodically, the Australian tunes were not as rich as the Irish prototype; their range was generally more limited. It was rather in their rhythmic lilt that they excelled. They have an ease about them that made them ideal for the singers. These were not songs that were intended for the concert hall; they were written to pass away the time of a night after a heavy day's work in the stifling heat of the shearing shed; they were written for the "bullocky" with a long road ahead and a slow team to drive, or for the boundary-rider with many long hours and days, even weeks, with no company but his own. For these men time meant little. Life was not the hectic rush that we modern city dwellers know. In these original tunes of the shearer-balladist we find reflected the easy philosophy of life that was characteristic of the wool period of Australian history, the attitude to life that has been immortalised by Tom Collins in "Such is Life." And this easy-going temperament was, in its turn, but a reflection of the land over which they travelled, a land of vast plains, of long horizons and sun-burnt vistas. The easy-going nature of the people and the timelessness of the country can be heard in these droll lilting tunes of the early Australian ballads.

THE WORDS

If there is an easy lilt ,in the tunes of these ballads, it is due to the fact that the verses to which the tune was wed, expressed the typically Australian attitude to life.' In these songs the ordinary man's reactions to the life he lived is described with simplicity, which was a characteristic of these pioneers and with a droll humour which has come to be regarded as the typical Australian form of humour. There is no doubt that these songs do portray the life of those connected with the wool industry, with the search for gold and with the pioneering on the land more vividly and certainly more intimately than a text-book survey of the period.

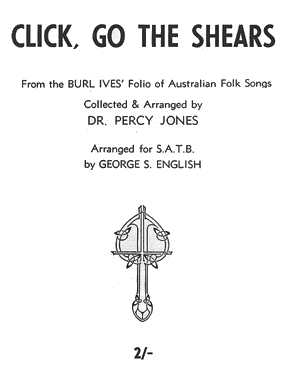

Take some of the songs of the shearers. Here is one which summarises the life they endured, the competition for the title of "ringer," the boy with the tar-brush in cases of the sheep being cut by the shears, the atmosphere of the shed and the spree that followed the receipt of cheques:

Out on the board the old shearer stands,

Grasping his shears in his long, honey hands,

Fixed is his gaze on a bare-bellied "Joe,"

Glory if he gets her, won't he make the "ringer" go.

Chorus:

Click go the shears boys, click, click, click,

Click go the shears boys, click, click, click,

Wide is his blow and his hands move quick,

The ringer looks around and is beaten by a blow,

And curses the old snagger with the blue-bellied "Joe."

In the middle of the floor, in his cane-bottomed chair

Is the boss of the board, with eyes everywhere;

Notes well each fleece as it comes to the screen

Paying strict attention if it's taken off clean.

The colonial experience man, he is there, of course,

With his shiny leggin's, just got off his horse,

Casting round his eye like a real connoisseur,

Whistling the old tune, "I'm the Perfect Lure."

The tar-boy is there, awaiting in demand,

With his blackened tar-pot, and his tarry hand;

Sees one old sheep with a cut upon its back,

Hears what he's waiting for, "Tar here, Jack!"

Shearing is all over and we've all got our cheques,

Roll up your swag for we're off on the tracks;

The first pub we come to, it's there we'll have a spree,

And everyone that comes along it's "Come and drink with me!"

Down by the bar the old shearer stands,

Grasping his glass in his thin honey hands;

Fixed is his gaze on a green-painted keg,

Glory he'll get down on it, ere he stirs a peg.

There we leave him standing, shouting for all hands,

Whilst all around him, every "shouter" stands

His eyes are on the cask, which is now lowering fast,

He works hard, he drinks hard, and goes to hell at last!

This song was sung to the well-known tune, "Ring the Bell, Watchman," and from practical experience, I have found it a most popular community, song with groups of young Australians.

Just one more picture of another aspect of the wool industry; it is a song that was very popular in the early days judging from the number of versions that have been sent to me, "The Old Bullock Dray." The bullock teams carried the wool from the sheep station to the nearest rail-head or port. The life was hard; always on the road, constantly faced with the problem of providing fodder for the team each night in country where grass was scarce; and these were only two of the bullockies' difficulties. There was always the problem of harnessing the team each morning and, worst of all, there were the many boggy roads that spelt disaster for the load. And when the dray sank to its axles in mud or marsh, one can sympathise with the drivers who had good grounds for using the language which has made their ability in this direction proverbial. Here are the words of the song:

Now the shearing is all over and the wool is coming down,

I mean to get a wife, me boys, when I go to town,

For everything has got a mate that brings itself to view

From the little paddy-melon to the big kangaroo.

Chorus:

Chorus:

So roll up your bundle and let us make a push,

And I'll take you up the country and show you the bush;

I'll be bound such a chance you won't get another day,

So roll up and take possession of the Old Bullock Dray.

I'll teach you the whip, and the bullocks how to flog,

You'll be my off-sider when I'm fast in the bog,

Hitting out both left and right and every other way.

Making skin, blood and hair fly around the Bullock Dray.

Good beef and damper, of that you'll get enough,

When boiling in the bucket such a walloper of duff,

My mates, they'll all dance and sing upon our wedding day

To the music of the bells around the Old Bullock Dray.

There'll be lots of piccaninnies, you must remember that,

There'll be "Buck-jumping" Maggie and "Leather-belly" Pat,

There'll be "Stringy-bark" Peggy and "Green-eyed" Mike,

Yes, my colonial, as many as you like.

Now that I am married and have picaninnies, three,

No one lives so happy as my little wife and me;

She goes out hunting to wile away the day

While I take down the wool in the Old Bullock Dray.

The attitude to the family life and the list of children's names leaves no doubt as to what blood ran in the veins of the composer!

Such are the typical songs of early Australia, and it would be a pity indeed if they were allowed to perish. If this country is to grow to manhood we cannot afford to neglect the songs of its youth. Although the two quoted are, perhaps, not suitable for schools, there are others that are, and it is about time that something was done to place Australian songs in the repertoire of school-music. In the many youth clubs that have sprung up in the last few years, there should be some of these early bush-songs in general use. For this reason, an edition of these songs is a matter that merits the attention of all concerned with the growth and development of this continent.

Notes

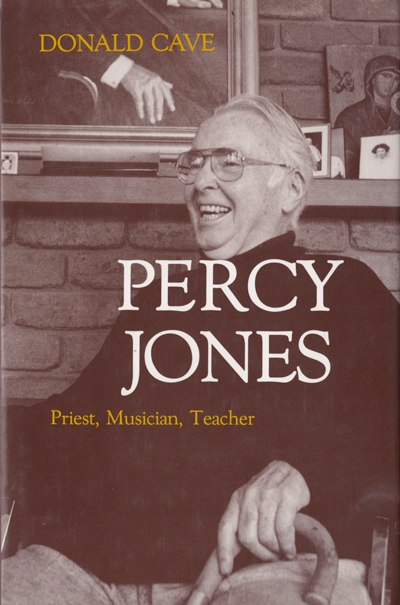

This artcle (minus the graphics) was first published in 1946 in the first edition of the magazine TWENTIETH CENTURY pp. 37-43